January 31, 2024

Short Polling: A Pragmatic Approach for Long-Running Requests and Asynchronous Notifications

Web applications demand responsiveness, but not all workloads fit neatly into the classic request-response model. When requests involve extended processing times or when we want the server to trigger updates asynchronously, short polling offers us a pragmatic and widely applicable solution. Although it looks simple on the surface, using short polling effectively requires us to understand memory usage, kernel involvement, and the right trade-offs between efficiency and responsiveness.

From Simple Requests to Long-Running Tasks

In a typical HTTP request-response cycle, the client sends a request and then waits until the server computes and responds. This model works beautifully for instant results. But consider uploading a large video, compiling code, or running a complex simulation: these operations take time. Holding an HTTP connection open wastes server memory, and threads could be tied up unnecessarily.

An analogy helps here. Imagine waiting at a doctor’s office: instead of standing at the counter constantly asking "is my appointment ready?", you check in, then return at reasonable intervals. Short polling follows this efficient check-in model—it reduces wasted effort while keeping progress visible to the client.

How Short Polling Works

The short polling cycle can be broken into well-defined steps, forming a structured communication dance between the client and server:

- Initial Request: The client starts the process by sending a request.

- Temporary Handle: Instead of the final result, the server promptly responds with an identifier (job ID, token, or session key).

- Follow-up Polling: The client periodically sends requests (polls) using that identifier to ask: "What’s the status?"

- Server Progress Updates:

- If the job is finished, the server returns the result.

- If still processing, the server replies with the current status.

Here’s a simple visual of the process:

sequenceDiagram

participant Client

participant Server

Client->>Server: Start processing request

Server-->>Client: Job ID

loop Periodic Polls

Client->>Server: Poll with Job ID

alt Task Complete

Server-->>Client: Final Result

else Still Processing

Server-->>Client: Status Update

end

end

Memory Layout and Kernel Involvement

Under the hood, short polling interacts with fundamental system resources. Let’s highlight a few aspects for software engineers:

- Kernel role: Every client request involves kernel I/O management—sockets, file descriptors, and buffers. Short polling multiplies these interactions since a single logical job can produce many small requests. Efficient kernel scheduling ensures that these requests don’t overwhelm CPU time.

- Memory implications: Each active connection—whether HTTP/1.1 keep-alive or HTTP/2 multiplexed streams—consumes memory in kernel space for buffers and bookkeeping. While short polling doesn’t hold connections open as long as long polling, the repeated creation and teardown puts pressure on memory allocation, especially under high concurrency.

- Caching and status storage: The server may store job state in RAM (in a hash map or task queue). Choosing the right memory structure is critical—e.g., sharded in-memory stores like Redis or lock-free queues inside Rust services can reduce contention.

An analogy here is like a train station with tickets: each "job ID" is a small stub in memory pointing to the passenger’s journey. The kernel is the railway operator ensuring that trains (I/O events) are scheduled without collisions.

Rust Example: Tracking Long-Running Jobs

Where relevant, we can implement job tracking in Rust using an in-memory store like HashMap<JobId, JobStatus>. Below is a simplified snippet showing how job status might be tracked:

use std::collections::HashMap;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use uuid::Uuid;

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

enum JobStatus {

Pending,

InProgress(u8), // percentage

Completed(String), // final result

}

struct JobStore {

jobs: Mutex<HashMap<Uuid, JobStatus>>,

}

impl JobStore {

fn new() -> Self {

JobStore {

jobs: Mutex::new(HashMap::new()),

}

}

fn start_job(&self) -> Uuid {

let id = Uuid::new_v4();

self.jobs.lock().unwrap().insert(id, JobStatus::Pending);

id

}

fn update_job(&self, id: Uuid, status: JobStatus) {

self.jobs.lock().unwrap().insert(id, status);

}

fn get_status(&self, id: Uuid) -> Option<JobStatus> {

self.jobs.lock().unwrap().get(&id).cloned()

}

}

This approach lets clients poll by supplying a JobId, while the server updates the in-memory store. In production, distributed coordination (e.g., Redis, Kafka, or a database-backed store) would handle resilience and scale.

Advantages of Short Polling

- Simplicity: Works with plain HTTP without the need for specialized real-time infrastructure.

- Resilience: Clients can disconnect and later resume polling with the same job ID.

- Compatibility: Can be layered on top of traditional web frameworks without complexity.

- Control of granularity: We can tune polling intervals to trade-off latency vs. resource footprint.

Limitations and Trade-offs

- Chattiness: Many small requests increase bandwidth and syscalls.

- Redundancy: If tasks complete rarely, most polls return "not ready yet," wasting cycles.

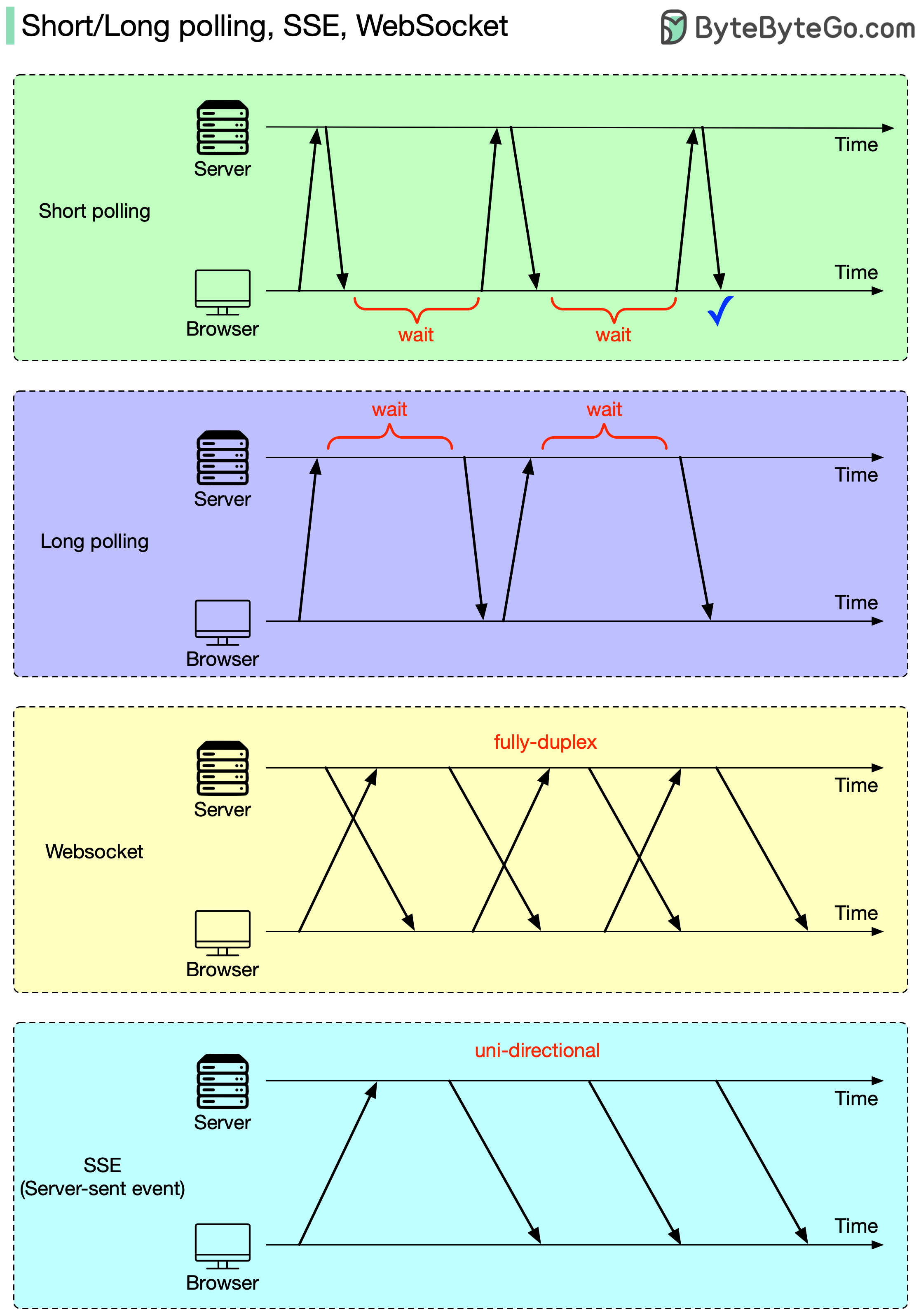

- Latency: Updates are near-realtime but never instantaneous compared to WebSockets or Server-Sent Events.

A good analogy here is checking a mailbox: short polling is like walking to your mailbox every 10 minutes. If the mail comes once a day, most trips are wasted. Event-driven protocols like WebSockets are akin to the postman ringing your doorbell when mail arrives.

When Should We Use Short Polling?

- Unpredictable job lengths — e.g., analytics queries, video encoding.

- Limited resources — when adding WebSockets/SSE is too complex or unnecessary.

- Resilient environments — where clients may drop in/out and resume later.

On the other hand, when true real-time responsiveness matters—like chat applications or live dashboards—more advanced protocols are better suited.

Conclusion

Short polling is like a bridge between the simplicity of request-response and the sophistication of event-driven protocols. It gives us reliability and simplicity at the cost of some efficiency. As software engineers, understanding its memory implications, kernel-level involvement, and trade-offs helps us apply it wisely where it fits best.

If you’re building long-running services today, don’t dismiss short polling—it might be the pragmatic option that balances complexity, performance, and user experience.

If you want to discuss how we can apply these techniques in your project, feel free to contact us.

Would you like me to also create an SEO meta description and suggested keywords for this blog post?